|

Hey! My name is Kyle Donnelly, a recent graduate from Texas A&M. This is my first time in the Antarctic, and I am stoked to be here. It’s also my first time south of the equator. This whole experience is crazy. The Antarctic is fascinating; It’s such a strange otherworldly environment, nothing like anything I've seen before. When I woke up, I looked out the porthole and saw icebergs for miles. After weeks out at sea with nothing on the horizon, the icebergs are a very welcome change. Earlier in the day I was out on deck working when I saw a decent sized iceberg approaching with some small black dots on it, and when it floated closer I saw that it was penguins! I wish I had a camera on me. Seeing penguins made my day. People here tell me that I’m going to get bored of seeing them but I don’t believe that’s going to happen. Its crazy seeing them for real, in the wild instead of in a zoo or aquarium. At the beginning of 2020 I would not have guessed I’d be seeing wild penguins by the end of the year, but here I am! It’s been a blast. The trip down here was full of different experiences. Sailing down here I was able to see the stars on cloudless nights, and the stars were the brightest I had ever seen them. The zodiac constellations in the sky at the time were beautiful and in full view; Capricornus the Sea-goat, Aquarius the water bearer, especially Sagittatius, the centaur hunter with his giant bow stretching across the night sky. Saturn, Jupiter and Mars were all visible as well; I was able to watch them slowly move across the night sky, seeing them in different positions each night. They say the stars at night are big and bright deep in the heart of Texas, but that doesn’t hold a candle to the beauty of the ocean sky at night. The change in the weather has been fun; A few weeks ago I was standing out on the bow in a t-shirt and light pants, now out there I need to get all bundled up if I’m spending any long period of time out there. It really started getting cold once we entered the straits of Magellan, which was easily the most beautiful scenery I’d ever seen. Beautiful white capped mountains accompanied by glaciers and clouds; we could not have asked for a more beautiful day to sail through the Straits. Last night we went through our first patch of sea ice, which was a much louder experience than I was expecting! It sounded like a giant white noise machine was outside the boat. I was in the galley eating when it happened the first time, and when I heard it I wasn’t quite sure what was happening, I assumed someone on the boat was moving heavy equipment across the floor. When it happened again the boat rocked a little bit; I got up and went to the porthole. Outside I saw a sea of ice chunks surrounding the boat. Sampling is going very well, we're seeing such fascinating creatures. There is a wonderful biodiversity here in the Antarctic, I've added some photos of my favorites like a large stony coral (Flabellum) we found, along with some very orange anemones and these neat snails (Harpovoluta charcoti) that have anemones (Isocisionis alba) on their backs! We're finding more neat stuff every day! I couldn’t be happier to be a part of the Icy Inverts expedition. This whole experience is one I’ll remember the rest of my life. Kyle Donnelly

0 Comments

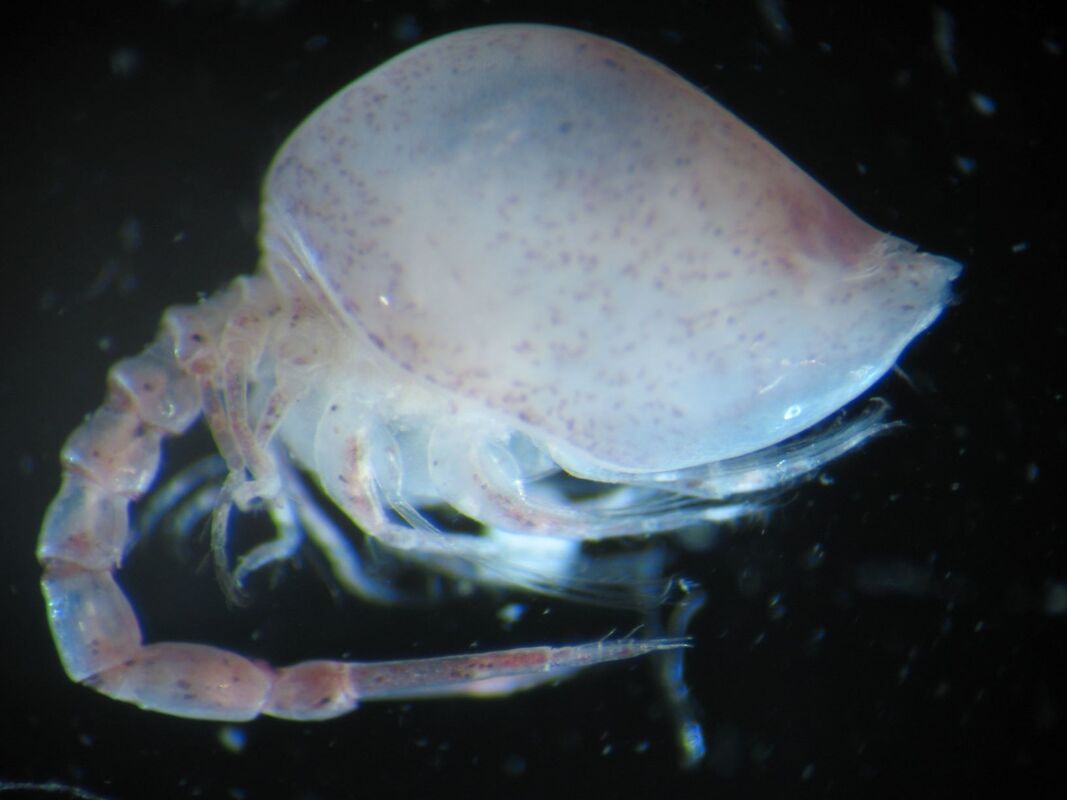

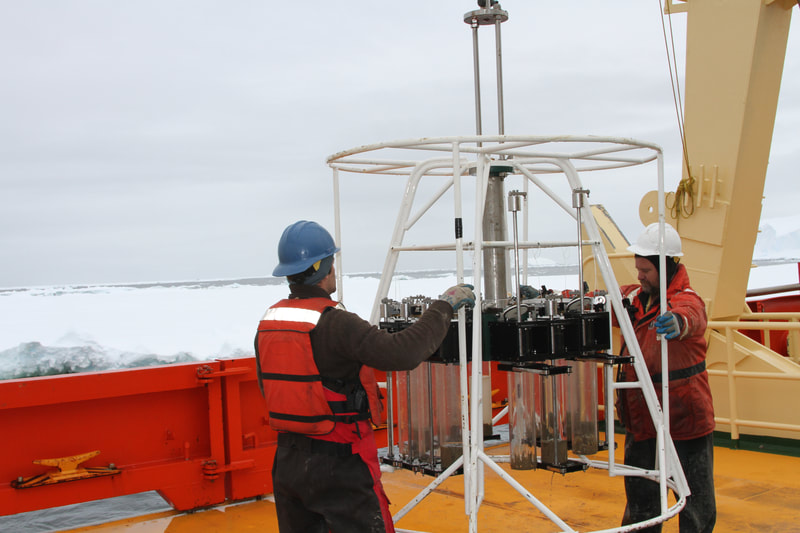

Latitude: -63 20.091 Longitude: -53 12.789 One of the most longstanding questions in biology is “why are there so many species?”. In fact, I strongly suspect most biologists are primarily motivated by this essential question once you take all the fancy words out. Charles Darwin answered this question in part with his theory of evolution but in doing so raised many more. Of particular interest to those of us currently onboard the RVIB Nathaniel B. Palmer is where are there so many species? Or, more formally, how is biodiversity distributed across space? One interesting trend in particular that has emerged is that, generally, the most species rich areas tend to be near the equator, with biodiversity dropping off as you move farther away toward the poles. This phenomenon is known as the latitudinal diversity gradient, or LDG for short. Scientists have known about the LDG for a long time, but we still don’t understand exactly what causes it. One theory is that environments are more unstable at extreme latitudes, with cycles of glaciation leading to higher rates of extinction, and therefore fewer species. Others think that the higher temperatures near the equator create faster generation times and mutation rates, resulting in higher rates of diversification, and therefore more species. Given the LDG one might expect Antarctica to be relatively species poor, however this is far from the case. In fact, there are some groups of animals, especially among marine invertebrates, that appear to follow the opposite trend, with more species the farther away from the equator they are. ~20% of all sea spider species, for example, are found in Antarctica. One of the trickiest things about studying the LDG is that it assumes we have a complete record of global biodiversity, when in fact ~80% of species remain undiscovered. Much of this undiscovered diversity is found in places that are very hard for humans to reach, such as Antarctica and the deep sea. Indeed, species are constantly being found in these environments making them some of the most active regions in the world for the discovery of new species. Antarctica in particular also has a large percentage of endemic species, that is species that are found nowhere else in the world, due to its unique environment as well as a circumpolar current that keeps it isolated from the rest of the world’s oceans. All these factors make Antarctica an extremely unique and interesting environment to study, especially if you are as interested in broad patterns of species diversity and evolution as I am. But before I can start the really fun work of exploring big ideas like the LDG I need to get a better idea of how many species there are in the first place. How can we say polar regions have fewer species when we have only just started looking for them? This is one of the reasons collection trips like this one is so important, discovering new samples from all across the animal tree of life will help us chip away at the ignorance surrounding one of the most enigmatic environments on the planet. As I write this, we are currently approaching our very first sampling site, a tiny strip of land off the very tip of the Antarctic peninsula. We will begin sampling around 0600 ship time, and since I am on the night shift (lucky me!) I will be on deck to start processing our first haul. After more than two months of quarantining and weeks at sea I am extremely excited to be one the privileged few that is able to perform the important work of exploring and documenting the unique organisms that inhabit one of the most extreme (by human standards at least) and rapidly changing environments on the planet. Kyle David Ph.D. student in the Halanych Lab Auburn University Latitude: -62 39.11 Longitude: -57 45.91 Hello! I’m Nusrat Noor, the Marine and Aquatic Invertebrates Collections Manager at the Auburn University’s Museum of Natural History. When I was first asked to join the Icy Inverts team I was beyond ecstatic. My first thoughts were…” wait really?? Is this actually happening right now? To me??” I quickly tried to bring myself back down from cloud nine and think about exactly what I would be agreeing to. I will be on a ship sailing down to Antarctica over the course of 3 months with a group of amazing scientists who share the same interests as me, going on an honest to goodness voyage! But on the other hand, I’m going to be stuck on a (large but not unlimited in size) ship for 3 months with people I had never met before. The worries running through my mind were never about if I was going or not because I knew from the moment I was asked, that unless something out of my control stopped me, I was going to be standing on the bow of the RVIB Nathanial B. Palmer on September 24th, come hell or high water. The worries running through my mind (other than the near sprint to get PQ’d on time) was, how do people deal with the mental side of things? I had never done anything like it before. So that’s what this blog post will be about because I know I was definitely curious about the mental health aspects of life on a research vessel and I hope you might be as well. I can’t speak for everyone’s experiences, but I can at least relay my own. In the beginning, there was a bit of stress, but it was always about getting through the next COVID-19 test and waiting on bated breath to find out about the results. But eventually the quarantine ended, and we were suddenly on our way with next to no internet and more time on our hands than most of us have ever had in our entire lives. Or at least extra time while also no longer being quarantined anymore. Much of that time was great for getting to know each other but there was also a lot more time to just be in our own heads. Being on the ship has paradoxically made me feel both constantly surrounded by people and also very isolated all at the same time. I missed my family, my friends, my bed, and Starbucks of all things. Eventually depression set in. Now don’t get me wrong, there was never a single moment when I regretted my decision or where I wouldn’t fight tooth and nail to make sure I stayed on this boat. And not being able to talk to the people I normally turned to, was a difficult adjustment to say the least. Suddenly I found myself thinking things like, “no one likes me” or “Everyone else is getting along and making friends but me”. These thoughts have been proving difficult to shake, despite continual invitations to game nights, inclusion during mealtimes, and spending more than a few nights up late, talking about interests and lives outside the ship. I’ve dealt with this long enough to be able to tell when I’m not quite in the right headspace but the people I normally talk to for help…well, I couldn’t reach anymore. So, what do you do when faced with this? You use what resources you have. For me, and for many other people on this ship, that resource is each other. No one understands an experience like this quite like the people who are going through it with you. When I began expressing my difficulties with dealing with these emotions, I found others struggling as well. And we helped pull each other out of the proverbial holes we’d unintentionally dug ourselves into and created a community that looks out for one another. There are still a few times where the depression and anxiety come back along with the intrusive thoughts but now, I know I’m not actually alone. Going on a trip like this is one of the most wonderous things I’ve experienced in my life but that doesn’t mean it can’t come with difficulties. The important thing to remember, as it often is, is that you’re likely not the only one, and reaching out helps more often than it doesn’t. Plus, it definitely helps to have the sampling finally begin! Coming up on the first site unfortunately wasn’t during my shift but that didn’t stop me from waking up after only 4 hours of sleep to see the sights of our first trawl. The excitement was just too much for me to handle! It felt absolutely perfect. The island was beautiful, I saw so many penguins, it was snowing in perfect flurries (almost as if I was suddenly transported to a Christmas movie), and there was waffle for breakfast (YUM!). But most of all, our first trawl came up with the most amazing animals I had been waiting to see for ages! I got to see and handle live invertebrates I had only either seen in museum specimens or in books. Sea spiders, sea cucumbers, brittle stars, tunicates, and bryozoans galore! Many of which were far larger than their counterparts in other parts of the world. Once they get pulled out of the water it’s a mad dash to get them sorted and processed quickly before the next site. It’s a whirlwind of activity and leaves you wanting more. I’ve just finished my first 12-hour shift and it was a struggle to make myself walk away from the table. It makes everything absolutely worth it. Nusrat Noor Marine and Aquatic Invertebrates Collections Manager Auburn University Museum of Natural History Hello from the Drake Passage! I’m Rebecca Varney, a PhD candidate in the Kocot lab working on chitons, molluscs with amazing iron-clad teeth. I hope you’ve had a chance to get to know some of our science team and their goals in earlier posts. I want to introduce you to the other people helping to make our scientific dreams a reality. (In my case, helping to dredge up some nice, velvety, clean mud). I had no idea how many other employees were necessary to our scientific mission, but after prepping the boat for Antarctica, it is easy to see the vital role that each one fills. We have two other teams on board: ECO, and ASC. The ECO crew runs the ship itself: the captain, mates, officers, and able-bodied seamen. The captain and mates allow us to visit the bridge and take in the views from somewhere warm, and they all have many stories of other voyages that have helped pass the transit time. A crew member is always cleaning or fixing, and you can tell that the work is done with pride and affection toward the Palmer herself. I can see why; we have all grown to love this ship. The ASC team is divided into Marine Laboratory Technicians, Marine Technicians, Information Technology Technicians, Electrical Technicians, and a Marine Project Coordinator to oversee it all. Our two Marine Laboratory Technicians (MLTs) are Diane and Jess. They oversee laboratory supplies, operations, and safety. Some of the science crew got to help them painstakingly count out supplies for each scientific mission (378 Whirl-Paks?!), and we all developed a lot of respect for the organization behind our functional lab spaces (look at all that gear!). Diane and Jess also keep us safe as we handle dangerous chemicals on a moving vessel, help us learn the intricacies of getting our samples safely home, and provide necessary enthusiasm and humor (especially from our “boat grandma” Diane). Our Marine Technicians (MTs) are Matt, Rich, Gavin, and Colin. They bring all the scientific gear onto the boat (via crane), ensure it is in working order (sometimes a big task!) and will be overseeing the deployment and retrieval of our epibenthic sled, Blake trawl, plankton net, CTD, and yo-yo cam. They also very scientifically tossed some gear off the boat into the ocean, deploying GPS-tracked “drifters” to measure ocean currents (we gave Colin an 8/10 for style). When they aren’t aboard a ship like the Palmer, the MTs fill their time with inspiring exploits. Matt, for example, helps run a non-profit called OceansWide, providing dive/safety training to youth with the goal of empowering students and helping them find productive career paths. Check it out here! Our Electrical Technicians (ETs), Alex and Sheldon, have been re-wiring equipment since before we got onto the boat. Sheldon has disassembled the GPS a number of times (it was accidentally teleporting us to Africa for a week). Meanwhile, Alex has a ‘yo-yo cam’ in about 50 pieces on his workstation, alongside “switchy mitch”, the yo-yo tester. I am floored by the sheer number of pieces of equipment that these techs know how to fix; it seems a lifetime of work just to learn to build one of them! The ETs’ troubleshooting is vital, and we appreciate them both. Though in complete honesty, I remain wary of Alex due to nerf-gun attacks and a propensity to blast Toto’s “Africa” every time the GPS jumped… Our IT staff, Matt P. and Andy, coordinate an intricate ballet of sensors that send information upstairs and do all the programming to keep the ship’s data available to all us scientists. They also portion out the satellite internet, which is how this blog is being posted. A parade of scientists came to both of them early on, desperate for advice on minimizing our devices’ background wifi connectivity. We are lucky to have our daily 750 Mb, but it goes fast! Matt P. also helped us run the ship’s on-board 3-D printer for the very important purpose of making Halloween cookie cutters! Last but certainly not least, our Marine Project Coordinator (MPC) Cindy is simultaneously warm and authoritative. If you pass her office, you may see her casually knitting a delicate shawl while she presses the MTs for precise information about the equipment loading process. I’m convinced that if a fruit fly landed on the bow of the boat, Cindy would know it was here, know its name, and know when it was scheduled to fly off. We have already benefitted a lot from her experience, and I know we will continue to grow more thankful for her firm grasp of all the inner workings of this expedition. We are fortunate to be surrounded by generous, kind people who are all so invested in helping our science happen. I learn more from ECO & ASC staff every day as they tolerate my endless questions about the ship, the equipment, and the process. Whatever cool invertebrates we get to meet on this voyage will be in large part thanks to them. Latitude: -53 53.278 Longitude: -71 07.253 It was the night before port call and all through the ship Not a crew member was stirring, not even for chips… Except 3 early career scientists sitting in the mess hall until sunrise. So maybe I’m not a poet, but crossing through the Straits of Magellan has to be one of the most poetic scenes I’ve ever experienced. On a whim, myself and a few other members of the science crew decided to stay up all night talking about how we got to where we are now (going to Antarctica right before and election in the middle of a pandemic?!), what we wanted out of the trip, projects for collaboration, and what we hoped to do after this experience. It dawned on us (pun absolutely intended) that if we could just make it to the first bits of daylight we would be able to see the beginnings of the straits and furthermore, the first bits of land we would see since we left Port Hueneme over 3 weeks prior. While this impromptu, late-night, science meeting was worth every minute for the awesome side projects (check back in later in the cruise for more from Team Bryozoan), it was a huge bonus to be able to see the giant straits appearing through the fog of early morning light. As soon as we were able to see the first signs of dawn through the mess port hole, we rushed back to our rooms to hurriedly throw on as many layers as we could find, grab cameras and binoculars, and race out to the bow. I felt very much like a child on a holiday. The water around us seemed almost turbulent and in the distance we could see just the faintest shadows of land on the horizon. As we continued to move inland, the land got closer, the fog cleared, the water calmed, and more and more detail of what was around us appeared. Towering mountains covered in snow in the background were juxtaposed with sloping rocky islands covered in greenery and rivers around us. A pod of orcas swam by off the port side of the ship, seals floated by, and more birds than I had seen in the last 3 weeks combined flew around us. The Jurassic Park theme song played in the background. As the morning progressed, and word spread around the ship, more and more of the crew joined us on the bow. By midday most members of the science crew were outside taking pictures as the straits closed in around us and we moved in closer to Punta Arenas. It may have had a bit to do with my total lack of sleep, but it was in these moments that this whole experience finally felt real. We were all really going to Antarctica. After over a month together, we’d all grown pretty close and the collective feeling on the boat was nothing short of amazed excitement. Pulling into Punta Arenas was just as exciting. The dock seemed to come out of the middle of downtown. The city of Punta Arenas moves up the hills around the port with wide streets gridding out the town and lighting the night. Most buildings have painted roofs or walls in shades of blue, red, pink, or yellow. Some of the architecture is new and modern and some looks like it may have been there for the last 100 years. All around the ship, hundreds of cormorants fly back and forth collecting bits of kelp and taking it back to their massive roosting area at the end of the docks. At night it’s clear there are things going on in the city. It was interesting to see streetlights and cars driving back and forth after being surrounded by almost no light pollution for so long. Our time in port was most characterized by rushing around and prepping the boat for FINALLY being able to depart to our destination. As we left Punta Arenas again, we got to go back out the way we came in, through the straits. Instead of getting closer and closer, we saw the cliffs and snow move farther and farther away. The mood on the ship as we moved out to sea was even more anxious and excited than it was coming in. We are finally within a week of starting our scientific portion of the trip… the main event… the big one… the moment we’ve all been waiting for! Our time thoroughly bonding as a crew prior to the science was at the worst of times overwhelming, and at the best of times some of the most fun I’ve ever had. Going from isolation to living with 40+ other people was an adjustment, especially with little internet and no specific job to do day-to-day. I’m still extremely grateful for the first half of this trip, spending time learning about all the animals we’ll see, getting to know my new colleagues and seeing parts of the Pacific so few are lucky enough to go through. All that said, I’m ready to get this show on the road and find some inverts! Caitlin Redak Ph.D. student in the Halanych Lab Auburn University Latitude: -53 53.278 Longitude: -71 07.253 Sunday, November 1, 2020 started a little on the grumpy side for me. I laid in bed with the debate of sleeping in or getting up. I forced myself out of bed and then walked out my room to grab some coffee. Half asleep, I walked by a colleague, who said, “Hey, did you see we are surrounded by land?” I was surprised as I didn’t think we would see land until the next day. I rushed outside to see the impressive mountains that lined the eastern side of the Straits of Magellan. What a breath-taking sight! I find it very interesting that I get quiet and a sense of amazement when observing the beauty of earth. Of course, after my initial amazement, I started thinking about the geology. Geology was one of my first scientific interests in my undergraduate studies. Geomorphology and structural geology were always fascinating and the Straits of Magellan had lots see. I even with limted internet, I found nice paper on the local geology (Diraison et al., 1997, Magellan Strait: Part of a Neogene rift system). Sedimentary, igneous, and metamorphic rocks all coming together in this region to show off the product of plate tectonics and mountain building. The added bonus is the glacial features that shape the mountains and valleys. All of this then leading to features that are driving erosion (waterfalls, rivers, and streams), which move sediment and nutrients down to the water to stimulate biological activity. This research expedition has certainly exposed a nice range of the scale of science. I can think of think of friends and colleagues working on the massive scales of mountains, which does connect to biodiversity. On our cruise, we have experts examining all sort of small life from bacteria and archaea to small inverts looking at changes, at even smaller scales, in DNA sequences or even the movement of electrons through redox reactions. These small (molecular) scale changes will help answer questions relating to climate change, evolution, and ecosystem processes, which is equally awe inspiring. Today we depart Punta Arenas, Chile and travel back through the Straits of Magellan making our way to Antarctica. Yes, I am excited to see the picturesque Straits again, but I am even more excited to get to Antarctica to start sampling. Dr. Deric Learman Central Michigan University All the final preparations are taking place across the different labs in the ship, making ready for the science that will be starting very soon. Equipment is coming on board and getting set up and secured, labs are getting organized. Sample handling plans are in place. Cold weather gear has been issued and tried on. Excitement is in the air! I personally am excited about getting started on my project. Cumaceans are small crustaceans (0.2-3 cm) that most people don’t know much about. Known as comma shrimp because their shape is like a comma, with a large carapace and slender abdomen, they can be quite abundant, and are eaten by seabirds in shallow areas and fish and even whales in deeper areas. It is difficult for cumaceans to be included in other types of work, such as ecology, because they are quite difficult to identify past the level of cumacean. The comma shape is distinctive, but to find out exactly what species it is can be challenging, as sometimes it means getting a very close look at a particular leg, or parts around the mouth that are very small. Adult males may not look very much like the females and juveniles, which is another challenge in identification. Thus, my overall project is to create identification resources for the cumaceans in the Antarctic and Sub-antarctic regions. My project involves taking samples from the bottom, preferably muddy/sandy areas and sorting out the cumaceans. The cumaceans will be photographed to show their colors while alive, for two reasons. Colors disappear very quickly after animals are preserved, and the colors are made by chromatophores, little patches that can expand or contract, but after the animal is preserved the patches are contracted, thus preserved animals lose both the color and the patterns of color across their bodies. Then I will identify the cumaceans, sort them into different species, take samples for DNA and RNA analysis, and preserve them. When I return to my lab in Alaska, I will describe any new species we find, unknown life stages (such as adult males), create reference collections, and write a monograph, a specialized type of book. Reference collections are sets of identified specimens kept in a museum that can be used to compare with new specimens, to make sure that the new identifications are correct. Samples will also be sent out for DNA barcoding, another type of identification tool. The monograph will include identification resources such as photos, drawings, and keys that will make it much easier to identify Antarctic and Sub-antarctic cumaceans found in the future. Latitude 53 10.2100S Longitude 70 54.3983W (Punta Arenas, Chile) In late December of 2012, I traveled to Chile to Board the RVIB Nathaniel B. Palmer and join my first Antarctic expedition. I was a Ph.D. student at Auburn University in Ken Halanych’s lab and joined him, his collaborator (and my former labmate in the Halanych Lab) Andy Mahon, and a team of researchers made up of their labs and collaborators. Fast forward about eight years later and now I’m a principal investigator (PI) myself and back aboard the ship with Ken, Andy, and our teams preparing to go to back to the Antarctic. This will be the fourth time for me, but I’m just as excited as I was the first time. In two days, we leave Punta Arenas and begin the last leg of our journey to Antarctica. We boarded the Nathaniel B. Palmer over 40 days ago (see photo) and I think I speak for everyone in the science party when I say that we are ready to get to work! Since we got to Punta Arenas, the ship has been a hive of activity with scientific gear and supplies from the warehouse being onloaded, inventoried, divvied out, and stowed. In addition to preparing for the current cruise, the US Antarctic Program (USAP) Marine Technicians and Marine Laboratory Technicians are preparing for other cruises on the ship that will take place after ours. Each scientific cruise has different objectives and that can mean very different sets of equipment and supplies need to be provided. Because we are collecting specimens, we have a lot of sampling equipment, containers, ethanol, and formaldehyde. For example, my team has 320 liters(!) of ethanol for preserving samples alone. Most of the supplies and equipment are on board the ship now, and yesterday I was reunited with some old friends: the epibenthic sled, the Blake trawl frames, and the sieving table. The epibenthic sled (aka epibenthic sledge or EBS; photo) is an instrument that is towed behind the ship to collect small animals living in the top centimeter or so of the sediment. It disturbs the top layer of the sediment with a chain and then the material that is stirred up is captured in what looks like a fine plankton net mounted inside the metal frame. The Blake trawl, which consists of a heavy metal frame (photo) and a net, is dragged along the sea bottom to collect larger animals living on top the sea floor. The sieving table (photo) consists of a series of stackable metal screens of decreasing mesh size that we can use to sieve mud brought up in trawls to reveal the animals within. My team will be using this equipment heavily during the cruise. In the lab, we’ve been busy securing microscopes and other equipment to the bench (photo). Because the ship may rock in weather, everything must be tied down or otherwise secured, especially fragile and expensive equipment like our microscopes. What are we doing with so many microscopes? My team is here because of an NSF-funded grant supporting research on the taxonomy and systematics of an unusual group of worm-like molluscs called aplacophorans (photos). Aplacophorans don’t look much like more familiar molluscs such as snails or clams, but if you look at them under a microscope (photo), you can tell they are related because aplacophorans have scales or spines made of calcium carbonate, the same material other molluscs’ shells are composed of. Worldwide, there are only a handful of experts actively working on this group and pretty much every time I sample where no expert has worked before, I find species that are new to science. Aplacophora is just one of dozens of groups of marine invertebrates with few or even no living experts studying them. So… Who cares? Taxonomy and systematics are fundamental disciplines in biology that provide information on the diversity of life on Earth, which is essential to the fields of conservation, ecology, and evolutionary biology. These fields offer the basis for all comparative studies, providing the names by which we call organisms, and a framework that explains their evolutionary relationships. Confronted with a vast number of undescribed species and high rates of extinction, we struggle with a lack of trained personnel and time to discover and characterize biodiversity. This work is especially important in Antarctica where climate change may lead to the extinction of many species, including some that will be lost forever before they were ever even known to science. I’m working to help bring the study small marine invertebrates like aplacophorans into the 21st century while training students who will hopefully go on to be the next generation of invertebrate biologists. My team will be working in the lab to sort samples under the microscopes, document virtually every specimen with high-quality photos, and collect material for taxonomic and genomic research. Specimens will be deposited in the Alabama Museum of Natural History for use in my lab's research but also any other researchers that wish to borrow specimens. Stay tuned for pictures of all the cool animals we find! Finally, I want to express how *incredibly* grateful we are to be able to conduct this work and give a huge shout-out to all the folks who made this possible. NSF, USAP, ECO, and The University of Alabama have gone above and beyond to make this research possible in the midst of a pandemic. Planning this kid of field work is always complicated and challenging and factors this year made things especially complicated. From the bottom of my heart, thank you to each and everyone of you. Dr. Kevin Kocot The University of Alabama Latitude: -53 10.2 Longitude -70 54.39 (Punta Arenas, Chile) We are starting our final preparations before heading south… and we are ready to head south. After a few more days in port, we will begin our 4-5 day crossing of the Drake Passage, one of the most notoriously rough areas in the world’s oceans. We are ready to begin science! Although there are four different National Science Foundation-funded projects on this expedition, they all have a common thread of exploring and discovering biodiversity on the Antarctic continental shelf, the sea floor region that extends from a continent to the steep slope that descends into the deep sea. The shelf of Antarctica is a bit different that in other regions of the world for a number of reasons. In most areas, the continental shelf is about 200m deep. However, in Antarctica, because of the weight of the ice pushing the continent down, shelf regions more typically about 400m deep. Also, because of the high latitude, the Southern Ocean region around Antarctica is bathed in nearly 24-hour light in summer and plunged into near 24-hour darkness in the winter. This light regime has a pronounced impact on the organisms. The well-lit summer months feed the region with energy for photosynthesis which is absent in the winter months. Thus, organisms in the region have evolved to handle this boom-bust energy cycle. At the end of the summer, much of the phytoplankton (small photosynthetic organisms in the water column) die and sink to the bottom, along with carcasses of zooplankton (small animals in the water column). This provides an incredible input of food to the organisms living on the sea floor, which can literally turn greenish from the input of phytoplankton – now called phytodetritus. In addition to depth and energy dynamics, the Antarctic shelf is different because of the constant presence of icebergs which, because of their size and weight, can extend to the sea floor and become “grounded.” Grounding and movement of icebergs is a perpetual source of disturbance for the communities surrounding the Antarctic. This constant disturbance has likely contributed to diversity and resilience of Antarctic organisms. However, the rate and magnitude of such disturbances are changing due to human-mediated climate change. With more icebergs calving off of glaciers, the benthos (the habitat on the sea floor) will possibly experience an elevated frequency of disturbance. What does this have to do with studying Antarctic biodiversity? Well, parts of the Western Antarctic are among the fastest warming regions on the planet. That not only means more disturbance, but organisms are shifting their biogeographic ranges because of changing water temperature. Importantly, because rates of climate change are greater in the Antarctic, organisms there can serve as a proxy for what to expect in other regions. However, in order to understand how organisms are responding, we first have to know who lives in these regions and their preferred habitat. At this point, I would remind the reader that although we think of the Antarctic as a singular place, the content covers 14 million square kilometers, a region bigger than Europe, Australia, or the contiguous United States. So of course, there are different coasts, different environments supporting different communities of organisms that are uniquely adapted to their own particular environment. Given the remote nature of the Antarctic, we still only have a poor understanding of its diversity. That is what we are here study. Dr. Ken Halanych Auburn University Latitude 53 10.2100S Longitude 70 54.3983W (Punta Arenas, Chile) Since we boarded the RV/IB Nathanial B. Palmer 43 days ago, we steamed south and arrived in Punta Arenas, Chile, a quaint South American city that originally served as a port of call for tourists and ships, particularly prior to the opening of the Panama Canal. Since then, it has gone through some changes but now, for us, it serves as a hub for refueling, resupply, and getting stores for our upcoming science from the warehouse here in Punta Arenas. Turns out, this whole endeavor is quite a logistical feat. Fuel, for example: we took on approximately 375,000 gallons of gas. This took about 17 hours to complete at the fuel pier. We’re spending the rest of this week at the resupply pier. The Marine Technicians and Marine Lab Technicians are making sure all of our science equipment and supplies are on the ship and are ready for us to use once we get to Antarctica. This includes all of our lab equipment and the nets, trawls, and collection gear we will be using. Other ship personnel are loading our food and other supplies to keep us well fed and happy (we’ve been unbelievably lucky throughout our long transit to get here…the crew have taken really good care of us…more on that in another blog!). Additionally, one other step of this port call is for us to get our ECW (Extreme Cold Weather) gear necessary for working in the Antarctic. During our transit down, we sent in sizes/measurements etc. to “order” the gear we will need…this includes deck boots, waterproof bibs, the all important rubber gloves and warm glove liners, and, among other things, “Big Red.” “Big Red” is the characteristic giant red parka that is issued upon request to scientists working in the U.S. Antarctic Program. This coat is unbelievably warm, possibly the most amazing coat I will ever have the opportunity to wear. There are some that hypothesize that it is so warm because it’s filled with unicorn fur. While this is questionable, it really is an amazing garment and part of the Antarctic experience. All of these logistical issues are no small feat. Each is critical to allow us to safely complete our scientific mission in the Southern Ocean. We will leave here on Sunday or Monday and begin our journey through the Drake Passage to our first field sites. One thing we can be assured of is that the crew of the ship has us ready to go. Dr. Andrew Mahon Central Michigan University Over the course of the last month at sea, we’ve experienced hot “summer-like” weather of the equator followed by a steady drop in temperature towards the “winter-like” temperatures of Antarctica. Additionally we’ve traversed over four time zones, thoroughly messing up any sort of circadian rhythm or sense of time. This can be seen around the boat with fewer and fewer bodies in the mess hall during breakfast time and heard by the whisperings of “is that clock correct?”. Many of the science crew are practically counting down the days until the time at which we will be able to start processing samples. During which, the idea of time will be once again turned sideways, as the science crew will be split into two teams as we start 24 hour ops. One team will have a 1 am to 1 pm shift while the other will have a 1pm to 1am shift. All the while, since it is getting towards summer in the Southern Hemisphere, the darkness of night will become continually briefer. Thus night time vs day time will likely become an abstract concept. Everyone on this ship has a list of taxa which they are most eager to see. While many of my friends back home asked about the excitement of seeing penguins, all the taxa which have been making the lists of the scientists on this ship are ones living below the ice. One of the things I am looking forward to seeing are the crinoids, particularly a certain feather star endemic to the Southern ocean, Promachocrinus kerguelensis. Crinoids are in a group called Echinodermata, some other taxa in this group are sea stars and sea urchins. The common name for crinoids like P. kerguelensis, which don’t have stalks, are feather stars. The reason I’m interested in seeing this odd looking echinoderm is because this was a taxa I studied during my master’s research and I have yet to see one alive. Secondly, I am excited to see examples of polar gigantism. Polar gigantism is the tendency for taxa in higher latitudes to be considerably larger than similar taxa found elsewhere. For example sea spiders (pycnogonids) are usually found no larger than 1 or 2 cm, but there is a common Antarctic sea spider that is the size of a dinner plate. Gigantism can be found in many different taxa and some others that we’ll likely see is gigantism in sea stars, isopods (like the rolly pollies one might find in their back yard), and the one I’m most excited about, Aplacophora. Aplacophorans are mollusks, similar to clams, chitons, and snails, however aplacophorans don’t have a shell. Instead of a shell, they are covered in little spines, called sclerites and have a worm shaped body. These are usually very small, not usually longer than a few millimeters to a centimeter or so. There is an Antarctic aplacophoran which is has been likened to the size of a bagel. Some of you might be wondering why Aplacophora. As a master’s student, I was exposed to Aplacophora when looking through sediment for invertebrates while on the R/V Falkor two years ago. As I peered down the microscope at the treasures that had been picked up by the ROV (Remote Operated Vehicle) earlier that day there was a very special organism that caught my eye. As it reared its head upwards to appear to be sensing its new surroundings, I caught sight of little papillae moving around which entranced me. It was love at first sight. It was the cutest organism that I had ever seen, which I quickly shared with any crew that were around at the time. Now as a first year PhD student, I have the privilege to focus on these little cuties. Emily McLaughlin Ph.D. student in the Kocot lab The University of Alabama Latitude: 30° 57.80’ S Longitude: 88° 30.56’ W

As a kid, I didn’t think I would be a scientist. I wanted to follow in my father’s footsteps and join the navy. I was entranced by my dad’s stories of his days as a submariner, thrilled by his seemingly endless handy fixes for everyday mechanical problems, always prefaced with his trademark “Want to see an old navy trick?” Of course I did—they felt close to magic, and the navy seemed to offer the possibility of travel and adventure that my life in a sleepy suburb sorely lacked. My dad, ever supportive, suggested that I could aim to be an officer in the navy. I had a target, then. In high school I joined my local Navy JROTC unit and focused myself on pursuing an appointment at the US Naval Academy. But like many teenagers, I found, explored, and ultimately followed other interests. By the time I was applying to colleges, I had turned from my dreams of a life at sea towards other horizons. I wasn’t exactly sure what course I was on, but I was more interested in computers and math than I’d ever been in my life, and more than anything else, I was ready to get out of my hometown and explore. I went to college out of state, in a city I had never visited before. The start of a long journey of discovering just what I wanted to do with myself and where in the world I wanted to be! I found a passion in the biophysics of protein folding and a lab I liked working in. I had my sights set on working on similar topics in grad school. But when I got there, I got the opportunity to work on a project on the biophysics…of squid eye lenses. It was too much to pass up. That project, and the work that followed, sent me back on a path I thought I had left behind. And ultimately, to this voyage. One of my favorite stories from my dad’s navy days is his crossing the equator at the international date line, a feat that came with a trial and a title—my dad is what they call a Golden Shellback. Several days ago, I was able to call my dad to wish him a happy birthday on the ship’s satellite phone and give him some unlikely news. We had recently crossed the equator ourselves, complete with a ceremony to celebrate the occasion. Against all odds, I’m a Shellback now too, and I’m on my way to the only continent he hasn’t been to. Thanks for the inspiration, dad. About me: Originally from Dallas, Texas, I studied biology at the University of Chicago (BA, ‘12) and finished my PhD at the University of Pennsylvania in 2018. After a working as a community scientist and K-12 educator with NYC-area nonprofit BioBus, I moved to Woods Hole, MA to work on a project with Dr. Jack Costello, studying the diet and swimming behavior of comb jellies (ctenophores) in the open ocean. We observe these animals directly by filming and sampling them while SCUBA diving. I have been on three previous oceanographic cruises in the Atlantic ocean, none of them nearly as intense as this one. You may think time passes rather slowly aboard a ship, tireless drifting South on the Pacific Ocean, towards our temporary destination within the Chilean fjords. You may also assume that with a ship filled with scientists, engineers, technicians, and other like-minded, sea-faring folk, we spend all our (copious) free time dreaming up new and exciting ways to science at sea; perhaps the next BIG scientific revelation is being contemplated here, in its infancy, and it’s just a matter of time. You may think we sit around, gabbing to one another about our favorite group of invertebrate weirdoes – who would win in a fight: the docile, shell-less molluscs called aplacophorans, or a closer relative to vertebrates and ever-squishy, uber-fragile critters commonly called acorn worms? I know my family wonders, “You’re spending almost two months at sea, and that’s just to get to where the actual research begins – so what do you do?” Well, reader, I’m here to tell you that not only do we absolutely do these things, but we’ve also become rather adept at making time for other forms of leisure aboard the RVIB Nathanial B. Palmer. Although the days are busy with folks digitally scribbling scientific manuscripts destined for peer-review while technicians aboard the ship prepare a variety of scientific instruments for our approaching Antarctic sampling frenzy, the evenings often take a different tone. Just two days prior to writing the present text, twelve of our most staunch scientific cruise members assembled in the third-floor conference room. No one spoke at first, but the collective knew they had only one month to solve a problem before we arrived at our destination across the Drake Passage. One month, that’s it. Any critical strategic mistakes and it could jeopardize any progress that had been made just moments prior. Every decision had to be carefully weighed against the suggestions of the rest of the party surrounding the conference table. There was dissent, there were conflicting ideals. The sleepy town of Grimmsgate was descending into ruin, and the decisions made at this conference room table would decide their fate. I am, of course, speaking of the Nathanial B. Palmer’s newest Dungeon’s & Dragon’s campaign (shout-out to Frog God Games and Wizards of the Coast)! Sure, I could tell you about the books being read in recreation, the various boardgames (of which there are many), movies and/or television we have been occupying ourselves with during the nights. Instead, let me provide you, dear reader, with some context to the colorful cast of characters that surround the 03 conference room table every-other night until we hit Antarctic waters. Led by myself and Damien Waits (this campaign’s Dungeon Master duo), our cast of adventurers feature a broad spectrum of science crew aboard the Palmer. Whether we consider Miso the Soup (an elf druid played by Nusrat Noor), Duke Oakly (a human sorcerer played by Will Ballentine), or Folgar Oris of the Frozen Mountain (a dragonborn barbarian played by Ken Halanych), our heroes are placed on common ground to fight the evils surrounding (and within) a ruined temple which has plunged into chaos. In addition to the ludicrous hijinks performed by the party (including speaking with river fish to determine the whereabout of an ogre, getting directions from horses, and sleeping on rooftops), we’ve also incorporated guest stars from even more members of the science team – playing characters such as the town’s unruly blacksmith (played by Candace Grimes), the excitable merchant (played by Kevin Kocot), and the wholesome inn-keep (played by Che Ka). As the party unravels the mysterious arcanum which has befallen the sleepy town of Grimmsgate, I’m happy to say that we work well not only as scientific colleagues, but also as a league of adventurers! With less than a month of time until our adventurers hang up their hats, cloaks, and arms for a new journey in Antarctica, we will be here around this table, every other night, solving the imaginary problems caused by witches and ghouls. Mike Tassia Ph.D. student in the Halanych Lab Auburn University Latitude: 16° 24.73' N Longitude: 110° 25.05' W Life at sea is full of surprises! As we move further south, I have been lucky enough to see sea turtles, flying fish, and even a few sea birds during our transit. The vastness of the Pacific gives me valuable perspective on the expansive habitat of Earth’s many marine organisms. The blue sky and rolling wake of the boat stretch for miles above deep stretches of Pacific open ocean. Few scientists have the opportunity to visit Antarctic waters, and even fewer have the fortune to accompany the vessel from the states all the way to Antarctica. However, our fortune breeds some boredom and now blazing heat as we have just crossed the equator yesterday! To escape the heat and stay productive, the Kocot lab has been training to use the macro-photography station that we procured for this trip. As our organisms of interest are often measured in micrometers or millimeters rather than centimeters or meters, obtaining high quality images can be difficult. Thus, we utilize high powered microscopes and specialized camera equipment. However, without specimens to test our skills as amateur macro-photographers we have gotten creative. A leftover piece of baby corn from the galley, or a dead beetle from the bow gives us ample subject matter to tinker with our setup. Now, thanks to ET (electronics technician) Alex Brett, we won’t have to start careers in vegetable photography! Alex cleans the filters of the boat’s oceanographic equipment every other day. These pre-filters trap planktonic animals that would otherwise interfere with the precise oceanographic measurements such as turbidity and are normally disposed of. To us in the Kocot lab they are the perfect subjects for practicing our photography skills! These small animals are just a slice of the diversity that passes under the NBP every day. I have no doubt the Antarctic animals will be even more charismatic! Nickellaus Roberts PhD Student University of Alabama Latitude: 16° 24.73' N Longitude: 110° 25.05' W A little about me: I am a first year PhD student at Central Michigan University working in the Mahon lab. My research focuses broadly on phylogenetics of Antarctic Pycnogonids (aka Sea Spiders). When I decided to study biology, I never thought I would be lucky enough to participate in a research cruise to Antarctica! It still seems unreal to me that I am on the way there and I will admit to pinching myself to make sure I am not dreaming all of this. Although we have been living on the Nathaniel B. Palmer since September 23rd, 2020, our crew has officially been out at sea for a little over a week now. This week has been full of adjusting to life at sea. Some of these adjustments include gaining our sea legs and getting used to the continuous motion of the boat moving with swells of the water, adjusting to the temperature changes as we continue to head south towards the Equator, and adjusting to life with a set amount of daily data (and soon to be almost no data). Most of us are used to having unlimited WiFi to connect our devices to and then going about our workday. This is the first time in many of our academic careers where we have had to worry about the amount of data that we are using. Many of us are learning how to ration out our data throughout the day so we still work efficiently during the day and be able to communicate to family and friends back home. One of my favorite parts of being out at sea is the lack of light pollution in the sky. The stargazing on the bow at night is incredible (as long as it’s a clear night). It’s hard to put into words how beautiful the night sky is, but it is definitely something I know I will never forget. I can (and have) sat outside for hours looking at the sky and watching the stars without getting bored. Along with stargazing at night, I had my first experience with bioluminescent organisms! When we look at the waves coming off the bow of the boat at night, we are often able to see little blue flashes of bioluminescence in the water, which is pretty neat to see in person! I also want to mention how cool the Nathaniel B. Palmer is to live on. The boat is 308ft long, with four decks, a Bridge and Ice Tower. There are five different lab spaces on the main deck, so there’s enough space for all the science work. The vessel also has a decently sized Galley and kitchen space (with many snacks and ice cream!), a gym, sauna, a conference room, a lounge on the 02 and 04 decks and multiple laundry rooms! We have two person cabins that each have their own bathroom and shower. We get three meals a day prepared for us, and the food has been really good so far. When it comes to field research vessels, the NBP one is an ideal one to spend a semester at sea aboard! Jessica Zehnpfennig PhD Student Central Michigan University Latitude: 19° 17.60' N Longitude: 111° 45.92' W The reality that I’m living on a boat and undergoing a literal voyage across three quarters of the globe to do research sampling in Antarctica during a pandemic has hit me numerous times a day for the last 3-ish weeks. Never in my wildest dreams had I expected to be invited on a research cruise to Antarctica. In fact, when I was approached over e-mail about it a few months ago, my response may have been, “WHAT.” You see, prior to this cruise, I had never even slept on a boat! I had no expectations for what life aboard the Nathaniel B. Palmer would be, especially for the stretches of time during quarantine and transit. Talking with the PIs, my science crew teammates, and the ASC (Antarctic Support Contract) crew has prepared me for things like what it will be like when the ship is breaking ice, how sampling will be conducted, and what it might be like going through the Drake passage. Fascinating to me are all the various habits we’ve all had to pick up. For instance, keeping doors closed/properly latched, storing all personal items in cabinets, thinking about how spilled liquids must be contained, and locking the watertight doors (that lead outside) behind you. Other aspects of life aboard the vessel are equally interesting. Going out on the bow to observe flying fish or see the Milky Way is a great way to break up or end the day. Being many miles offshore with only the ship lights, we are able to see the Milky Way, constellations, and stars that make up the night sky, usually hidden due to city light pollution. As for sampling once we make it to Antarctica, my specialty is on phylum Bryozoa (AKA moss animals), a group of mostly marine filter-feeding, colonial animals. Most of my fieldwork experience is in habitats close to shore, such as floating docks and tide pools. I’ve identified bryozoan species for a few projects in a few various parts of the world and I’m so excited to add Antarctica to that list! Megan McCuller Collections Manager, Non-molluscan Invertebrates North Carolina Museum of Natural History Latitude: 30° 52.98' N Longitude: 117° 15.25' W So far… We have prepared, packed, self-isolated (14 days), quarantined (19 days), passed not 1, not 2, but 3 (yes, 3!) COVID tests, secured our equipment, and now (finally!) we have departed Port Hueneme (PTH) on the Nathaniel B. Palmer (NBP). From California, we are headed south to Punta Arenas, Chile (PA) where we will resupply and refuel for our trip to Antarctica. We have been quarantined in PTH for just over two weeks where we have been able to get acquainted with our new home for the next few months while it is not moving. While in quarantine, we have kept our masks on and socially distanced whenever possible. We are currently in a full steam to PA for about 4 weeks. It was nice at PTH because we had been able to contact family, friends, loved ones, and see our beloved critters that we had to leave behind (both furry and otherwise) with relatively normal means. While we were at PTH, we saw some of the famous California fog that creeps over the coast in the afternoon and sometimes lingers on nearby vessels (see eerie photo). Some of us have also been having an arts and crafts time each day to relax and sometimes familiarize ourselves with the creatures we’ll see in Antarctica (crinoid drawing). It is a little odd, but the six months before our departure (I typically refer to them as the COVID times) helped prepare us for the over two months we will spend aboard the NBP. If you think about it, we spent several months barely going anywhere and being isolated from people we would normally see daily. Fast forward to the present, we have been fortunate enough to participate in this incredible opportunity to board a ship with strangers (for some of us) and embark on this journey to a continent few get to visit. In PTH, we were able to unpack and stow equipment for travel which resulted in a lot of questions to the people who have been on the ship and to Antarctica before because most of us have not. The stowing of equipment forced some of us to take a short knot-tying course with the help of those more experienced. After we collect samples in Antarctica, we will ship them back to the states in fancy coolers that we bring to far below freezing temperatures with the use liquid nitrogen (Kyle and Jess with their scientific cauldron). We have also been breaking up the workdays in quarantine playing card games and watching movies in the lounge. A little more about me: I just finished my PhD at Texas A&M University at Galveston, where I focused on the ecology of the bearded fireworm. I exposed the worms to low oxygen conditions to look at how they responded. If you’re curious about that, please let me know because it is one of my favorite topics. Currently, I am working on previously collected data from an Antarctic brittle star as a postdoctoral researcher in Dr. Ken Halanych’s Lab at Auburn University. I am also working on identifying animals from photo transects collected in the Southern Ocean during previous cruises. In the past, I have focused on annelids (worms) in the Gulf of Mexico and southeast Atlantic Ocean, so I am VERY excited to learn about all these new animals in this new (and very cold) ecosystem (check out the seafloor photo with echinoderms). Last night, we had our first sunset at sea on our southbound steam, and it was definitely one to remember. Wormly, Dr. Candace J. Grimes Postdoctoral Researcher Auburn University When I decided to be a marine biologist at the age of 10, I knew it would involve playing with organisms that live in mud, but I did not anticipate Antarctica! Commonly known as comma shrimp, cumacean crustaceans are found throughout the world’s marine benthos, but not many people study them. Studying cumaceans has allowed me to travel to many places in the world, from above the Arctic circle in Norway to New Zealand, normally with plenty of time to prepare. In contrast, the process of joining this cruise was a whirlwind, with 3 days to prepare before starting the in-home quarantine process. Luckily, finding a microbe-sitter for my sourdough starter didn’t take long. Getting to San Francisco and starting the quarantine process was actually a relief, despite the covid testing. However, now I will be doing two things I have long wanted, but never expected: crossing the equator on a ship, and going to the Antarctic. I am looking forward to getting to know the other scientists on board, learning more about many other groups of invertebrates, and of course collecting many wonderful colorful cumaceans!

Dr. Sarah Gerken Professor University of Alaska Anchorage The planning and organization leading up to a cruise is an intense process. Being at sea there is no possibility to just pop into the store, be it marine hardware or grocery, to get what you need. So, the packing and planning for a typical cruise is very deliberate and organized. When we were asked to deploy in September instead of November, the entire packing process was accelerated and squeezed into a just a few months. But the process got completed, 20 participants cleared the medical requirements to deploy so that we have a full scientific complement, and here we are sitting on the RVIB Nathaniel B. Palmer in Port Hueneme California. The timeframe for embarking was pushed up significantly because we are sailing to Antarctica from California, not the usual Punta Arenas Chile. Not surprisingly, most countries are not keen on foreign nationals (aka potential COVID risks) flying into the country. This added over a month of steaming and two port stops before heading to the Antarctic. Oh, and there is also the 14 days of quarantining on the ship before ever leaving port in the first place. Currently, we are waiting on the results from the second of three rounds of COVID testing which took place after transiting on the ship from San Francisco to Port Hueneme. (We were happy that all were negative for the first COVID test in San Francisco). When we docked yesterday at an otherwise empty pier in Port Hueneme, the doctor had rolled up on the dock in a small pickup truck and had hand-carriable tool cases filled with swabs for a nasal COVID test, vials and personal protective equipment. One by one we filed down the gangplank, off the boat, and got our brains tickled. We all cried, some of us more than others. While we wait on the results of testing round 2, we started unpacking all the equipment that we so tediously organized and packed back at our home institutions. This is our last chance to make sure that we have everything we need. Again, this time it is different. If we have forgotten something, we cannot just run off the ship while in port because we cannot risk being exposed to COVID-19. The US Antarctic program has an amazing support staff that can help us get items, but even if get things to the boat, they have to be quarantined for a few days to make sure no active virus can make it onto the boat. While sequestered, we are still taking all the needed precautions known to reduce the risk of transmission: wearing face masks, social distancing and washing hands. Only once we are out at sea, after more than two weeks of quarantining and three negative COVID tests, will be able to relax some of these measures. Nevertheless, the science crew is excited, despite the bouts of anticipation and relief. The Kocot lab eagerly set up their microscopes in a lab where they will spend many hours sorting material, even though we are still many weeks away from sampling. Most of the researchers have brought analyses, papers or other work-related projects from home. During our time quarantining at Port Hueneme, which will last until October 8th, we will continue to prep the ship for science, but we will also finish up projects that we brought from home. One other point of excitement it the opportunity to sit and talk science with colleagues and banter ideas back and forth. After 6 months of COVID isolation, when most of our collegial interactions have been restricted to Zoom or WebEx, the in-person discussions will be welcome. Of course, there will be breaks for an occasional card game or some Dungeons & Dragons, or reading that book one has been putting off. Dr. Ken Halanych Professor Auburn University The packing has begun… am I overpacking? What am I forgetting? Will I really need that? Is there space for another bag of coffee? Do I have enough movies/games/books to keep me occupied in my down time?

One would think that after a number of years working on Antarctic research projects, I would be better prepared to pack for a trip. However, this trip is a little different. Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, we cannot travel directly to Punta Arenas, Chile to board the research vessel. This time we have to fly to San Francisco, CA to board the ship and take it all the way south to Antarctica! This means spending nearly three months on the ship, non-stop! Packing is challenging because we will go through so many different climates on our way to get to Antarctica… temperate, tropics, and then moving into the more polar regions. With a limited amount of baggage space, clothing choices are much more important this time for sure. Additionally, I have to make sure that I have enough work to stay busy and productive during the trip until we get to our Antarctic field sites, along with making sure I have enough things (movies, books, music, games) to keep myself sane during the extensive amount of down time! In terms of a timeline, we leave home on September 20, 2020 and we will board the ship sometime around September 24, 2020 in San Francisco, CA. From there we will travel to Port Hueneme, CA on September 25 and will stay there in quarantine until October 8, 2020. After this, we will head south for Punta Arenas, Chile where we are due to arrive on November 2, 2020. In Punta Arenas, we will be refueled and take on supplies and equipment. In order to maintain quarantine, no personnel from our teams will leave the ship while in port. After a few days, we will begin our trip across the Drake Passage to Antarctica to start our field work, with an estimated return date to Chile of December 15, 2020. More soon.... Dr. Andrew Mahon Professor of Biology, Central Michigan University When I started at Central Michigan University (back in 2011), I would have never imagined conducting microbial research on Antarctic benthic sediments. Joining a research expedition to Antarctica would have been unimaginable. It’s fun looking back to see that a friendly science conversation with Andy Mahon (who started at CMU at the same time) initiated this all off. Our original intention was not to find a collaborative research project, but to talk about science. While I was hearing words, like pycnogonid, for the first time, our conversation also mentioned sampling sediments for meiofauna. A few more conversations later, Andy and his collaborators (including Ken Halanych) offered to collect some sediment samples for my lab, which then generated new collaborative research ideas, new projects/manuscripts, and even successful (and a few unsuccessful) grant funding. Our current work will utilize metagenomics and metatranscriptomics, coupled with microcosm experiments, enzyme assays, and geochemical data to describe how microbes degrade complex organic matter in Antarctic sediments. The upcoming expedition will expand our samples collection from the Ross and Amundsen Sea to the Weddell Sea. I am excited for the upcoming opportunity to continue to explore microbial metabolism in sediments in Antarctica, and of course talking science during our expedition.

Don't forget to follow @Icy_Inverts_AU, @CMU_Antarctica, @kmkocot, @Geomicro_DRL and #IcyInverts on Twitter! Dr. Deric Learman Professor Central Michigan University From 20 September, 2020 to 18 December, 2020, our team of researchers will be sailing on the R/V Nathaniel B. Palmer to sample marine invertebrates living in waters off Antarctica. Our team will consist of researchers from Auburn University, The University of Alabama, Central Michigan University, and other institutions. This research will help improve understanding of the biodiversity and evolutionary history of marine invertebrates living in Antarctic waters. This will be my fourth Antarctic research cruise but it never gets old. I. AM. SO. EXCITED. Below are some of my favorite photos from cruise on the same ship that I joined in 2013. Please check back here often for regular updates once our cruise begins and be sure to follow @Icy_Inverts_AU, @CMU_Antarctica, @Geomicro_DRL, @kmkocot, and #IcyInverts on Twitter! Kevin Kocot Assistant Professor University of Alabama

|